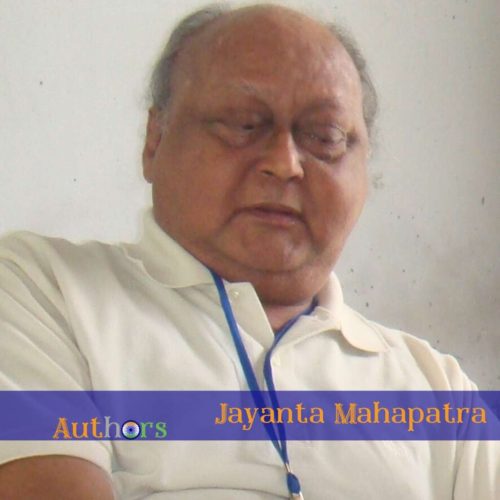

Name: Jayanta Mahapatra

Born: October 22, 1928, Cuttack, Odisha, India

Died: August 27, 2023, Cuttack, Odisha, India

Occupation: Poet, Essayist, Translator

Genre: Poetry, Prose, Translation

Famous Works: Relationship (1980), A Rain of Rites (1976), Temple (1989)

Notable Awards: Sahitya Akademi Award (1981), Padma Shri (2009), Jacob Glatstein Memorial Award

Early Life, Education & Personal Details

Jayanta Mahapatra’s formative years in Cuttack, Odisha, were shaped by a profound tension between his Christian identity and the Hindu-majority cultural milieu surrounding him. Born on October 22, 1928, into a middle-class family that had converted to Christianity several generations earlier, Mahapatra grew up in a household where faith was a private refuge and a social marker of difference. This religious duality—rooted in a colonial-era conversion that distanced his family from Odisha’s dominant Hindu traditions—imbued his childhood with a sense of alienation. As he later reflected, “I felt like an outsider in my own land, caught between the cross and the temple tower” (Mahapatra, Interview 152). His family’s Christianity, a legacy of British missionary influence, positioned them as a minority in a region steeped in Hindu rituals, festivals, and temple culture. The Jagannath Temple in Puri, a pilgrimage site and spiritual fervour, loomed large in his imagination yet remained symbolically inaccessible, amplifying his sense of dislocation.

Education:

Jayanta Mahapatra’s academic journey began in Cuttack, Odisha, where he attended Stewart School, an English-medium institution that laid the foundation for his bilingual literary sensibility. He pursued higher education at Ravenshaw College (now Ravenshaw University), graduating with a degree in physics. Later, he earned a Master’s degree in the same discipline from Patna University, Bihar, which equipped him for a career in academia. His scientific training as a physicist profoundly influenced his poetic vision, blending empirical precision with metaphysical inquiry. In 2006, Utkal University conferred an honorary D.Litt for his contributions to Indian literature, cementing his dual identity as a scientist and poet (Das, Poetry 15; Samal 42).

Mahapatra’s early education at English-medium schools, including Stewart School and Ravenshaw College, further complicated his cultural identity. While English instruction opened doors to Western literary traditions—he immersed himself in Eliot, Pound, and the metaphysical poets—it also deepened his estrangement from Odia’s vernacular culture. This linguistic bifurcation mirrored his religious struggles: he navigated Bible studies at home while witnessing the vibrant Hindu festivals that animated Cuttack’s streets, such as Durga Puja and Rath Yatra. In Relationship, his Sahitya Akademi Award-winning collection, he grapples with this duality:

“The temple bells rang / but their sound could not enter my prayer” (Temple),

A well-read critic or even an ordinary reader perusing Mahapatra’s poetry for pleasure could observe a metaphor for his unresolved tension between Christian devotion and Hindu cultural resonance, as noted very well by Bijay Kumar Das (Poetry 34).

Critics like Ashok Bery note that Mahapatra’s poetry often “oscillates between reverence and rebellion, faith and doubt,” reflecting his fraught relationship with both religious traditions (Bery 305).

Personal Life and Marriage:

Mahapatra married Jyotsna Mohapatra, with whom he shared a quiet, private life in Cuttack. Though details about their marriage remain sparingly documented, his poetry occasionally hints at the interplay of personal and creative realms. Poems like A Father’s Hours (1976) reflect on familial bonds and the passage of time, suggesting that domestic life informed his meditations on love, loss, and legacy. His role as a husband and father coexisted with his academic responsibilities at Ravenshaw College, where he taught physics until his retirement in 1986. Colleagues noted his disciplined routine: mornings dedicated to teaching and afternoons to writing, a duality that mirrored his thematic preoccupations with fragmentation and unity (Padihari 171).

Balancing Science and Poetry:

Mahapatra’s late entry into poetry—publishing his first collection at 43—underscored the tension between his scientific career and literary aspirations. While physics provided financial stability, poetry became an emotional outlet, a space to reconcile his “divided self” (Mahapatra, Interview 155). His marriage and familial obligations likely shaped his empathetic portrayal of human relationships, particularly in works like Relationship (1980), which explores intergenerational ties and cultural inheritance. Despite his global acclaim, Mahapatra remained rooted in Odisha, his personal and poetic worlds intertwined with the landscapes and struggles of his homeland.

Legacy of Solitude:

Known for his introspective nature, Mahapatra often described himself as a “lonely seeker of truths,” a disposition reflected in his poetry’s meditative tone (King 197). His personal life, marked by simplicity and introspection, mirrored the quiet intensity of his verses, leaving a legacy as profound as it is understated.

A reserved temperament compounded his sense of isolation. Shy and introspective, Mahapatra sought solace in Odisha’s landscapes—the Mahanadi River, the ruins of Konark, and the cyclonic storms that battered the coast. These natural elements became metaphors for inner turmoil in his work. In A Rain of Rites, he writes:

“The river’s silence carves through my bones, / a godless hymn to all I cannot name” (A Rain of Rites)

In the above line, readers can observe a blending of ecological imagery with spiritual ambiguity (Prasad 187). The Hindu temples he observed from a distance, such as Puri’s Jagannath and Bhubaneswar’s Lingaraja, symbolised a cultural wholeness that eluded him, later evolving into motifs of fragmented identity in poems like Dawn at Puri:

“A skull on the holy sands / tilts its empty country towards hunger”

Critics observe that rituals of death and salvation underscore his existential dissonance (King 198).

Professionally, Mahapatra’s career as a physics professor at Ravenshaw College (1950–1986) introduced another layer of duality. While science provided intellectual rigour, poetry became his emotional outlet.

Literary Career

Jayanta Mahapatra emerged as one of India’s most significant English-language poets, carving a distinct niche through his introspective exploration of Odisha’s cultural ethos, existential dilemmas, and postcolonial identity. His literary career, marked by a late start, meteoric rise, and gradual retreat from the limelight, reflects the evolving landscape of Indian English poetry in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Early Publications: A Delayed Yet Prolific Beginning

Mahapatra’s literary journey began unusually late. After decades of teaching physics at Ravenshaw College, Cuttack, he published his debut poetry collection, Close the Sky, Ten by Ten, in 1971 at 43. This was swiftly followed by Svayamvara and Other Poems (1971), which introduced his signature style—lyrical yet brooding, rooted in Odisha’s landscapes yet universal in its existential queries. His early work, including A Father’s Hours (1976) and A Rain of Rites (1976), established his preoccupation with time, memory, and cultural dislocation themes. Poems like Dawn at Puri and Hunger juxtaposed Odisha’s spiritual heritage with stark social realities, earning him recognition for his unflinching humanism.

Recognition and Fame: The Peak of Acclaim

The 1980s marked Mahapatra’s ascent to national and international prominence. His seminal collection Relationship (1980), a meditation on identity and heritage, won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1981—the first ever awarded for English poetry. This accolade cemented his status as a pioneer of Indian English verse. Critics lauded his ability to weave Odia myths, such as the legends of Puri’s Jagannath Temple, into a modernist framework, creating what Bruce King termed “a new Indian English idiom” (King 194).

During this period, Mahapatra co-founded the literary journal Chandrabhaga (1979), a platform that nurtured emerging Indian poets and solidified his influence. His international acclaim grew with the Jacob Glatstein Memorial Award (USA, 1975) and the Japan Foundation’s Visitor Award (1990). Works like Life Signs (1983) and Dispossessed Nests (1986) further showcased his evolving style, blending fragmented narratives with ecological and existential imagery.

Fading into the Background: Shifting Trends and Legacy

By the 1990s, Mahapatra’s prominence began to wane as newer voices in Indian English poetry, such as Vikram Seth and Jeet Thayil, gained traction. His later collections, including Temple (1989) and A Whiteness of Bone (1992), retained his thematic depth but faced criticism for their perceived obscurity and repetitive motifs. Critics like Arvind Krishna Mehrotra argued that his “muted brooding” occasionally lapsed into redundancy, overshadowed by the rising tide of urban-centric, globally resonant poetry (Mehrotra 56).

Mahapatra’s turn to Odia-language poetry in the 1990s—publishing works like Bali (1993) and Nirbhaya (1998—further diverted attention from his English oeuvre. Despite accolades such as the Padma Shri (2009) and honorary doctorates, his later English collections, such as Random Descent (2005), struggled to recapture the critical ardour of his early career. Yet, his legacy endured through academic scholarship, with scholars like Bijay Kumar Das framing him as a “poet of the soil” whose work bridged regional and global sensibilities (Das 24).

Conclusion: A Quiet Retreat

Mahapatra’s death in 2023 marked the end of a career of quiet perseverance. While his later years saw diminished public visibility, his contributions remain foundational to Indian English poetry. His exploration of cultural hybridity, existential angst, and Odisha’s mythic past continues to resonate, securing his place in the postcolonial literary canon.

Publications by Jayanta Mahapatra

Poetry in English:

- Close the Sky, Ten by Ten (1971)

- Svayamvara and Other Poems (1971)

- A Father’s Hours (1976)

- A Rain of Rites (1976)

- Waiting (1979)

- The False Start (1980)

- Relationship (1980)

- Life Signs (1983)

- Dispossessed Nests (1986)

- Selected Poems (1987)

- Burden of Waves and Fruit (1988)

- Temple (1989)

- A Whiteness of Bone (1992)

- Shadow Space (1997)

- Bare Face (2000)

- Random Descent (2005)

Translations and Prose:

17. Door of Paper: Essays and Memoirs (2007)

18. Eight volumes of translated Odia poetry, including works of Gopabandhu Das and Sitakanta Mahapatra.

Odia-Language Poetry:

19. Bali (1993)

20. Tikie Chhaati (1994)

21. Nirbhaya (1998)

22. Maya Darpana (2003)

Mahapatra’s five decades-old oeuvre remains a testament to his relentless quest for meaning amid the contradictions of identity, faith, and belonging.

Themes in the Poetry of Jayanta Mahapatra

Jayanta Mahapatra’s poetry is a rich exhibition of themes that intertwine personal introspection, cultural identity, and socio-political critique. Rooted in the landscapes and myths of Odisha, his work navigates the complexities of post-colonial India while grappling with universal existential concerns. Below is a detailed analysis of his major themes, supported by critical perspectives and textual examples:

1. Orissan Landscape and Cultural Identity

Mahapatra’s poetry is deeply anchored in the geography and mythology of Odisha, with recurring references to Puri, Konark, and the Mahanadi River. These locales are not mere backdrops but active symbols of cultural memory and identity. For instance, in Dawn at Puri, he writes:

“A skull on the holy sands / tilts its empty country towards hunger”(A Rain of Rites).

This juxtaposition of sacred ritual and stark poverty underscores his preoccupation with the place as a site of spiritual and material conflict.

Critics like Bijay Kumar Das note that Mahapatra’s work “acclimatises an indigenous tradition to the English language,” creating a hybrid idiom that bridges regional specificity and global resonance (Das, Poetry 24). His use of Odia myths, such as the legend of Lord Jagannath, reflects what Bruce King terms as a “post-colonial assertion” of cultural autonomy (King 194). For Mahapatra, the temple town of Puri becomes a metaphor for cultural wholeness and fragmentation, mirroring his duality as a Christian in a Hindu-majority milieu.

2. Social and Cultural Critique

Mahapatra’s poetry confronts the harsh realities of Indian society—poverty, corruption, and gender inequality. In Hunger, he unflinchingly depicts exploitation:

“I hear the soft grunt of the fisherman’s daughter / as the men rifle through her skeletal flesh” (A Rain of Rites).

This visceral imagery critiques systemic oppression, particularly the marginalisation of women.

Syamsundar Padihari observes that Mahapatra’s “tragic consciousness” is unparalleled in Indian English poetry, as he lays bare the “incongruities and lacunas” of Indian culture (Padihari 173). Poems like The Stories in Poetry lament societal apathy toward child labour, blending humanistic empathy with stark realism. His critique extends to colonial legacies; in The Abandoned British Cemetery at Balasore, he writes:

“Crosses lean like forgotten debts, / their shadows tracing the map of my divided heart” (Temple),

symbolizing the lingering scars of colonialism.

3. Existential and Humanistic Concerns

Mahapatra’s work is suffused with existential angst, exploring themes of guilt, isolation, and the search for meaning. In Relationship, he grapples with identity:

“For it seemed to be a time / when waters flow past without their purposes” (Relationship).

This reflects his meditative tone, termed “languid in its metaphysical poise” by critic Dilip Chitre, as he navigates the dissonance between self and society.

Madhusudan Prasad identifies a “tragic vision of life” in Mahapatra’s poetry, where personal pain intersects with collective suffering (Prasad 182). His later collections, such as Random Descent (2005), delve into semantic indeterminacy, mirroring postmodern fragmentation. Critics like Syd Harrex liken his Jungian archetypes to the “grass-roots of the emotions,” where myths serve as conduits for primal human experiences (Harrex).

4. Time, History, and Myth

Mahapatra intertwines temporal dimensions, using myth to interrogate contemporary realities. In The Temple Road, Puri, he writes:

“Stream of common men’ on the road to the temple / and the form of their prayer” (The Temple Road, Puri),

blending ritualistic past with present-day struggles.

Ashok Bery highlights Mahapatra’s “oscillation between reverence and rebellion” as he re-enacts myths to critique modernity (Bery 305). For instance, Bali (1993) reimagines the mythological sacrifice to allegorise societal exploitation. This interplay of myth and history, as Subrat Kumar Samal notes, reflects a “quest for roots” in a globalised world (Samal 48).

5. Religious and Cultural Duality

Mahapatra’s Christian upbringing in a Hindu-majority Odisha engendered a lifelong tension between faiths. In Temple, he writes:

“The temple bells rang / but their sound could not enter my prayer” (Temple),

capturing his alienation from Hindu rituals.

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra observes that Mahapatra’s “divided heart” mirrors India’s post-colonial identity crisis (Mehrotra 56). This duality fuels his exploration of hybridity, as seen in Lost:

“My tongue stutters in two tongues, / each word a betrayal” (Bare Face),

where linguistic and spiritual conflicts coalesce.

6. Language and Form

Mahapatra’s bilingualism and scientific training shaped his poetic form. His free verse, marked by fragmented syntax and striking imagery, mirrors existential dislocation. In The Logic, he juxtaposes scientific precision with metaphysical doubt:

“The algebra of grief defies solution, / yet I count the stars like a clerk of heaven” (The False Start).

Critics like Bruce King praise his “passionate precision” in crafting a “new Indian English idiom” (King 194). However, his complexity has drawn criticism; Mehrotra argues that his “muted brooding” occasionally lapses into redundancy (Mehrotra 56).

To summarise this section, Jayanta Mahapatra’s poetry is a profound exploration of identity, place, and existential despair, rendered through a unique synthesis of Odia myths and modernist techniques. Bijay Kumar Das asserts that his work is a “voyage within” that bridges regional ethos and universal humanism (Das 89). While later works faced critiques of obscurity, his legacy as a “poet of the soil” endures, offering a nuanced lens into India’s post-colonial psyche. Through themes of cultural duality, social critique, and existential inquiry, Mahapatra cements his place as a cornerstone of Indian English literature.

Critical Evaluation of the Style of Jayanta Mahapatra’s Poetry

Jayanta Mahapatra developed a distinctive style marked by its interplay of regional specificity, existential introspection, and linguistic innovation. His work navigates the complexities of postcolonial identity, blending Odisha’s cultural landscape with universal existential themes. Below is a critical examination of the key stylistic elements in his poetry:

1. Linguistic Synthesis and Bilingual Duality

A unique synthesis of the English language and Odia cultural ethos characterises Mahapatra’s poetry. While writing in English, he infuses his verse with Odia myths, rituals, and idiomatic expressions, creating a hybrid linguistic register. For instance, in Dawn at Puri, he juxtaposes the sacred imagery of the Jagannath Temple with the stark reality of poverty:

“A skull on the holy sands / tilts its empty country towards hunger”(A Rain of Rites).

This blending of the sacred and the profane reflects his negotiation between colonial linguistic legacies and indigenous traditions. Critics like Bruce King note that Mahapatra’s style “acclimatises English to an indigenous tradition,” resisting Western literary norms while asserting a postcolonial identity (King 194). However, this duality occasionally leads to critiques of obscurity, as seen in his use of untranslated Odia terms (e.g., Bali) that may alienate unfamiliar readers.

2. Fragmented Syntax and Free Verse

Mahapatra predominantly employs free verse, rejecting traditional metrical structures to mirror the disintegration of traditional values in modernity. His fragmented syntax and nonlinear narratives evoke a sense of existential chaos. In Relationship, he writes:

“For it seemed to be a time / when waters flow past without their purposes”(Relationship).

The disjointed cadence reflects the destabilising effects of urbanisation and cultural erosion. Scholar Bijay Kumar Das argues that Mahapatra’s free verse embodies a “voyage within,” capturing the fluidity of memory and identity (Das 24). Yet, some critics, like Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, critique his “muted brooding” as occasionally redundant, suggesting that his stylistic experimentation risks incoherence (Mehrotra 56).

3. Imagery and Symbolism

Mahapatra’s poetry is rich in sensory imagery drawn from Odisha’s ecology—rivers, monsoons, and temple architecture. These elements function as symbols of cultural memory and existential angst. In The Lost Children of America, he juxtaposes the Mahanadi River’s flow with the dislocation of diaspora:

“The river’s silence carves through my bones, / a godless hymn to all I cannot name” (A Rain of Rites).

Such imagery bridges the personal and the collective, as noted by Syamsundar Padihari, who identifies a “tragic consciousness” in Mahapatra’s portrayal of Odisha’s socio-spiritual conflicts (Padihari 173). His use of paradox—e.g., “holy sands” juxtaposed with “hunger”—underscores the tension between tradition and modernity.

4. Temporal and Mythic Layering

Mahapatra’s work often intertwines mythic pasts with contemporary realities, creating a palimpsest of time. In The Temple Road, Puri, he reimagines the pilgrimage to Jagannath as a metaphor for existential quests:

“Stream of common men on the road to the temple / and the form of their prayer”(The Temple Road, Puri).

As Ashok Bery observes, this layering of myth and history reflects a “postmodern indeterminacy,” where time becomes cyclical rather than linear (Bery 305). His later collections, such as Random Descent (2005), amplify this fragmentation, mirroring the dislocation of globalised identities.

5. Socio-Political Critique

Mahapatra’s style integrates sharp socio-political commentary, particularly on poverty and gender inequality. In Hunger, he employs visceral imagery to critique exploitation:

“I hear the soft grunt of the fisherman’s daughter / as the men rifle through her skeletal flesh”(A Rain of Rites).

His unflinching realism, coupled with lyrical restraint, emphasises the ethical urgency of his themes. Critics like Subrat Kumar Samal praise his “humanistic empathy,” though some argue that his focus on despair risks overshadowing resilience (Samal 48).

6. Meditative and Introspective Tone

A hallmark of Mahapatra’s style is his meditative tone, often tinged with melancholy. Poems like Evening reflect on mortality and memory:

“Searching the landscape for the leaf’s green, / the stone’s ochre, for what I would not make of myself”(Relationship).

This introspective quality, termed “languid in its metaphysical poise” by Dilip Chitre, invites readers into a contemplative space, though it occasionally verges on solipsism (Chitre).

7. Evolution and Later Works

In his later Odia-language poetry (e.g., Nirbhaya, 1998), Mahapatra shifts toward greater regional specificity, using transliterated Odia terms and folk rhythms. As Bijay Kumar Das notes, this bilingual evolution marks a “return to roots,” though his English works remain central to his legacy (Das 89).

In short, Mahapatra’s style is a complex tapestry of linguistic hybridity, fragmented form, and mythic resonance. While his work has been critiqued for its density and occasional obscurity, its contribution to postcolonial literature lies in its unflinching exploration of identity, place, and existential despair. By intertwining Odisha’s cultural landscape with universal themes, Mahapatra crafts a unique idiom that challenges and enriches Indian English poetry.

Influences

Mahapatra’s work intersects with T.S. Eliot’s existentialism and Nissim Ezekiel’s urban realism. His mythopoeic vision aligns with A.K. Ramanujan, yet his Odia roots distinguish him. Critics liken his juxtaposition of “concrete and abstract” to metaphysical poets like Donne (Bery 302). Postmodern indeterminacy, as in Random Descent, reveals affinities with Latin American magic realism.

Views on Poetry

Mahapatra viewed poetry as a “voyage within” to reconcile identity and heritage. He asserted:

“The air of the place is under my skin… the place chooses me to write” (Mahapatra, Interview 155).

Jayanta Mahapatra’s perspective on poetry is deeply rooted in his dual identity as an Odia poet writing in English and his existential engagement with cultural and spiritual themes. He viewed poetry as a medium to explore the interplay between myth, history, and personal identity, often describing it as a “voyage within” to reconcile the fragmented self with the external world (Das, Poetry 24). For Mahapatra, poetry was not merely an aesthetic endeavour but a moral and spiritual quest to grapple with the “incongruities and lacunas” of Indian society (Padihari 173).

Mahapatra believed that poetry should reflect the cultural values of its milieu, and his work often draws on Odia myths, rituals, and landscapes to articulate a distinct Indian sensibility. He saw himself as “an Oriya poet who incidentally writes in English,” emphasising the importance of regional identity in shaping his poetic voice (Mahapatra, Interview 155). This bilingual duality allowed him to bridge local and global concerns, creating a hybrid idiom that resonates with Indian and international audiences.

However, his insistence on poetry as a medium for existential inquiry sometimes led to critiques of obscurity. Critics like Arvind Krishna Mehrotra argue that his “muted brooding” occasionally results in overly abstract or inaccessible verse (Mehrotra 56). Despite this, Mahapatra’s commitment to portraying the “essence divine” in human relationships and his exploration of themes like time, memory, and suffering underscore his belief in poetry’s transformative power.

In essence, Mahapatra’s views on poetry reflect his broader philosophical outlook—a synthesis of regional rootedness, existential angst, and universal humanism. While his approach has been critiqued for its complexity, it remains a cornerstone of his enduring legacy in Indian English literature. It is also to be noted that Mahapatra tried his best to reject the colonial frontiers and linguistic hierarchies. He sought to “acclimatise an indigenous tradition to English” (Das, Poetry 24), crafting a hybrid idiom transcending nostalgia.

Later Life and Legacy

In later years, Mahapatra returned to Odia, publishing four poetry volumes (1993 onward), reaffirming his regional roots. Despite debates over his “obscurity,” his legacy as a pioneer is secure. Scholars like Bruce King laud his “unique Indian English idiom” (King 195), while The Hindu eulogised him as “the poet of Odisha’s soul.”

His death in 2023 marked the end of an era, but his exploration of “time, myth, and silence” (Samal 45) ensures his place in the postcolonial canon.

Mahapatra left an indelible mark on Indian English poetry, establishing himself as a pioneer who bridged regional and global literary traditions. His legacy is defined by his profound exploration of Odisha’s cultural and spiritual ethos, existential themes, and postcolonial identity. Mahapatra’s work, rooted in Puri, Konark, and the Mahanadi River landscapes, redefined Indian English poetry by infusing it with Odia myths and local idioms, creating a unique hybrid idiom that resonated globally.

His seminal collection Relationship (1980), which won the first Sahitya Akademi Award for English poetry, cemented his status as a trailblazer. Critics like Bruce King laud his ability to “acclimatise English to an indigenous tradition,” asserting a postcolonial identity distinct from Anglo-American norms (King 194). Mahapatra’s introspective style, marked by fragmented syntax and vivid imagery, captured the complexities of time, memory, and cultural dislocation, influencing subsequent generations of poets.

Despite critiques of obscurity, his humanistic empathy for marginalised voices—particularly women and the impoverished—remains a hallmark of his work. Poems like Hunger and Dawn at Puri exemplify his unflinching critique of societal inequities, blending lyrical beauty with ethical urgency.

Mahapatra’s bilingualism, evident in his Odia-language poetry (e.g., Bali, 1993), further enriched his legacy, showcasing his commitment to regional identity. His founding of Chandrabhaga, a literary journal, provided a platform for emerging Indian poets, fostering a vibrant literary community.

In sum, Mahapatra’s legacy lies in his ability to intertwine the personal and the universal, the regional and the global, creating a body of work that continues to inspire and challenge readers. As Bijay Kumar Das aptly notes, Mahapatra remains “a poet of the soil,” whose voice endures as a testament to the transformative power of poetry (Das 89).

Criticism, Controversies, and Ambiguities

Though Mahapatra’s legacy will remain revered by the inhabitants of the Indian English Poetry Society, his writings do have shortcomings that many critics and scholars have highlighted occasionally. Let me discuss a few here.

1. Obscurity and Inaccessibility

One of the most persistent critiques of Mahapatra’s poetry is its perceived obscurity. His dense, fragmented syntax and reliance on abstract imagery often alienate readers unfamiliar with Odia myths or his existential preoccupations. For instance, in Relationship, lines like “For it seemed to be a time / when waters flow past without their purposes” (Relationship) exemplify his elliptical style, which critics argue prioritises ambiguity over clarity. Arvind Krishna Mehrotra contends that Mahapatra’s “muted brooding” occasionally lapses into redundancy, making his work inaccessible to a broader audience (Mehrotra 56). While his complexity reflects his engagement with postcolonial identity and existential angst, it risks overshadowing the emotional immediacy of his themes.

2. Overemphasis on Despair and Pessimism

Mahapatra’s poetry is often critiqued for its relentless focus on despair, poverty, and existential suffering. Poems like Hunger and Dawn at Puri depict stark realities with unflinching honesty, but critics argue that this emphasis on tragedy can overshadow moments of resilience or hope. Syamsundar Padihari notes that Mahapatra’s “tragic consciousness” dominates his oeuvre, leaving little room for optimism or redemption (Padihari 173). While his humanistic empathy for marginalised voices is commendable, the absence of counterbalancing themes risks reducing his work to a monochromatic portrayal of suffering, limiting its emotional range.

3. Repetition and Stylistic Redundancy

Another charge against Mahapatra’s poetry is its repetitive motifs and stylistic monotony. Critics argue that his reliance on recurring symbols—rain, stone, silence—and themes of cultural dislocation can feel formulaic over time. Bruce King observes that while Mahapatra’s early work is groundbreaking, his later collections, such as Random Descent (2005), often retread familiar ground without significant innovation (King 197). This repetition and fragmented syntax can dilute his poetry’s impact, leading to stylistic stagnation critiques. Despite these charges, Mahapatra’s contributions to Indian English poetry remain foundational, even as they invite ongoing critical scrutiny.

Critical Analysis of Mahapatra’s Political Engagement and Selective Silence

Jayanta Mahapatra’s involvement in the “Award Wapsi” movement, a protest against the Narendra Modi government’s alleged intolerance, has drawn significant criticism, particularly in light of his perceived silence during the Kashmiri Pandit Exodus of 1990. This selective engagement with political issues raises questions about the consistency and depth of his activism and the motivations behind his participation in what many critics have termed a politically charged movement amplified by left-leaning intellectuals and opposition parties.

Silence During the Kashmiri Pandit Exodus

The Kashmiri Pandit Exodus of 1990, which saw the forced displacement and persecution of nearly 300,000 Hindus from the Kashmir Valley by radical Islamic militants, remains one of the most tragic episodes in India’s post-independence history. The violence, marked by targeted killings, rape, and the desecration of temples, was a blatant assault on the cultural and religious identity of the Kashmiri Pandit community. Despite the scale and severity of this tragedy, Mahapatra’s poetic and public voice remained conspicuously absent during this period. Critics, including noted journalist Arnab Goswami, have pointed out this silence as a glaring contradiction in Mahapatra’s otherwise vocal stance on issues of intolerance and violence.

Mahapatra’s silence during the Exodus is particularly striking, given his thematic preoccupation with human suffering and marginalisation in his poetry. Poems like Hunger and Dawn at Puri demonstrate his ability to confront systemic oppression and societal apathy with unflinching honesty. Yet, his failure to address the plight of the Kashmiri Pandits—a community subjected to ethnic cleansing and cultural erasure—suggests a selective engagement with issues of violence and intolerance. This inconsistency undermines the moral authority of his later activism, raising questions about the criteria he employed to determine which injustices warranted his attention. Critics argue that his silence during the Exodus reflects a broader trend among Indian intellectuals to prioritise certain narratives of victimhood while ignoring others, particularly those that do not align with their ideological leanings.

Participation in the “Award Wapsi” Movement

Mahapatra’s participation in the “Award Wapsi” movement, which saw several artists and intellectuals returning their awards to protest the Modi government’s alleged intolerance, further complicates his legacy. While the movement was framed as a moral stand against rising communalism and violence, critics have argued that it was disproportionately amplified by left-leaning intellectuals and opposition parties, often overlooking similar or worse instances of intolerance under previous governments. Despite his silence during the Kashmiri Pandit Exodus, Mahapatra’s involvement in this movement has been interpreted by some as politically motivated rather than rooted in a consistent ethical framework.

The “Award Wapsi” movement was criticised for lacking grassroots resonance and inability to connect with the lived realities of ordinary Indians. Many viewed it as an elitist gesture disconnected from the concerns of the broader population. Mahapatra’s participation in this movement, while aligning him with a certain intellectual and political cohort, also exposed him to accusations of hypocrisy. Critics argue that his activism during this period lacked the depth and nuance of his poetic engagement with social issues, reducing his stance to a performative gesture rather than a substantive critique of systemic intolerance.

Moreover, Mahapatra’s selective activism raises questions about the role of intellectuals in shaping public discourse. While his poetry often grapples with themes of cultural dislocation and existential despair, his political engagement appears inconsistent and ideologically driven. This inconsistency not only diminishes the credibility of his activism but also highlights the challenges intellectuals face in maintaining a balanced and principled stance in a polarised political landscape.

Jayanta Mahapatra’s legacy as a poet and intellectual is undeniably significant, but his selective engagement with political issues complicates his standing as a moral voice. His silence during the Kashmiri Pandit Exodus and his participation in the “Award Wapsi” movement reveals a troubling inconsistency in his activism. While his poetry continues to resonate for its profound exploration of identity and suffering, his political choices invite critical scrutiny, underscoring the complexities of navigating the intersection of art, ethics, and ideology in a deeply divided society.

Conclusion

Jayanta Mahapatra’s universe of imagery, metaphors, the conflict between the mind and the heart and an ever-elusive reconciliation between his wavering faith in the civilisational legacy of Hinduism and generational tenets of Christianity will be long-etched on the pages of the history of Indian English literature. Mahapatra’s style of writing, marked by its meditative tone and dramatic monologues (and dialogues), has impressed critics in India and the English-speaking parts of the world. Though a late entrant into the world of verse, Mahapatra never felt let out except on the occasions he wanted to. While his political ideologies, activism and participation may well be looked into time and again by different persons (with their prerequisite of biases), Mahapatra’s poetry will have its appeal in a secular and uniform form – a call for all to ponder, interpret and immerse themselves into the abstract created by the void of Mahapatra’s undying search of his soul in the holy streets of Odisha!

Works Cited

- Bery, Ashok. “Imagery and Imagination in the Poetry of Jayanta Mahapatra.” Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia, edited by Sheldon Pollock, University of California Press, 2003, pp. 298-310.

- Chaudhuri, Rosinka. A History of Indian Poetry in English. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Das, Bijay Kumar. Poetry of Jayanta Mahapatra. Atlantic Publishers, 1992.

- Das, Bijay Kumar. Poetry of Jayanta Mahapatra. 4th ed., Atlantic Publishers and Distributors, 2007.

- King, Bruce. Modern Indian Poetry in English. Oxford University Press India, 2001.

- Krätli, Graziano. “Keki Daruwalla and Gieve Patel.” Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia, edited by Sheldon Pollock, University of California Press, 2003, pp. 310-327.

- Mahapatra, Jayanta. Interview with Abraham. Indian Literature, vol. 40, no. 4, July-Aug. 1997, pp. 149-57.

- Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna. An Illustrated History of Indian Literature in English. Permanent Black, 2003.

- Padihari, Syamsundar. “Jayanta Mahapatra: The Poet of the Soil.” Indian Literature, vol. 51, no. 3, May-June 2007, pp. 168-76.

- Prasad, Madhusudan. “‘Caught in the Currents of Time’: A Study of the Poe1ry of Jayanta Mahapatra.” Journal of South Asian Literature, vol. 19, no. 2, Summer-Fall 1984, pp.181-207.

- Samal, Subrat Kumar. Postcoloniality and Indian English Poetry: A Study of the Poems of Nissim Ezekiel, Kamala Das, Jayanta Mahapatra and A.K. Ramanujan. Partridge Publishing, 2015.

- Sinha, Arnab Kumar, et al., editors. Contemporary Indian English Poetry and Drama: Changing Canons and Responses. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019.

Written by Alok Mishra for The Indian Authors

—-